TATB Hall of Famers Curt Warner and Kenny Easley

The on-field matchup between the Seattle Seahawks and Pittsburgh Steelers is, by our early estimation, too close to call. The Steelers have superior talent; the Seahawks have a superior coach. It should be a doozy of a Super Bowl.

In matters of tradition and football pedigree, however, the Black 'n' Gold beats the Green and . . . uh, Green in a gruesome mismatch.

Consider: The Steelers have four Lombardi Trophies and an all-time roster loaded with famous names: Bradshaw, Swann, Stallworth, Blount, Lambert, Von Oelhoffen.

Legendary Seahawks? Let's see, there's Steve Largent, one of the three or four finest receivers of all time, and absolutely the greatest among those who require SPF 4000 sunscreen at the beach. And there's . . . well, that's just about it.

Largent. A list of one.

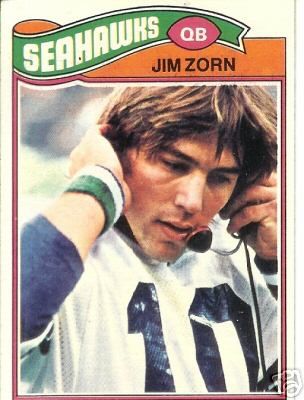

Now, I suppose you could qualify popular, mediocre quarterbacks Jim Zorn and Dave Krieg as "well known," if a few thousand passing yards from "legendary." And current coach Mike Holmgren may yet build a Hall of Fame resume; as it is, he deserves plaudits for overcoming enormous biological odds to become a football coach instead of a walrus. (Confession: I plagiarized that last line from my good friend Yuri Pride, whom I'm fairly sure is the only sportswriter-turned-doctor this planet has ever known.)

Now, I suppose you could qualify popular, mediocre quarterbacks Jim Zorn and Dave Krieg as "well known," if a few thousand passing yards from "legendary." And current coach Mike Holmgren may yet build a Hall of Fame resume; as it is, he deserves plaudits for overcoming enormous biological odds to become a football coach instead of a walrus. (Confession: I plagiarized that last line from my good friend Yuri Pride, whom I'm fairly sure is the only sportswriter-turned-doctor this planet has ever known.)Otherwise, the Seahawks' status through the years has been as a football footnote. Like Michael Jackson (the moonwalkin' freakshow, not this guy), they haven't done a damn worthwhile thing in about 20 years. Their last playoff victory before this season came in 1984, when they beat the Los Angeles Raiders in an AFC wild card game. No, they weren't habitually awful like the Cardinals, or comically inept like the pre-Peyton Colts. They were just sort of there, a nondescript tribute to mediocrity. Heck, they could have folded, and the news may not have spread past Tacoma.

You almost wonder if certain players' legacies have suffered by association to the franchise. Sure, there was only one Largent, but I can think of two Seahawks who were stalwarts in their day but have been all but forgotten except by the most ardent NFL Films junkies.

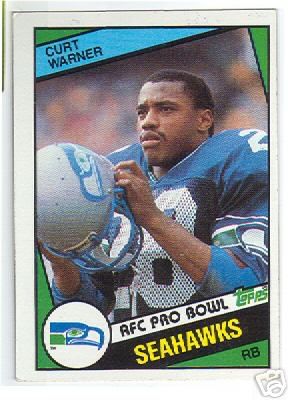

I give you Curt Warner.

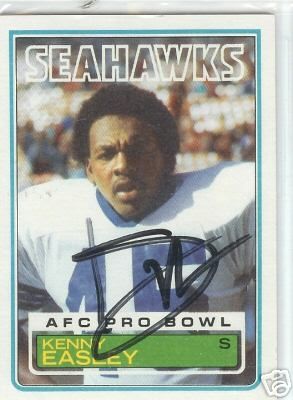

I give you Curt Warner.I give you Kenny Easley.

Do their names ring a bell? I imagine they do, even though I suspect you haven't heard them in years. Warner was the greatest running back in franchise history until Shaun Alexander scribbled his name all over the record books.

A smooth, deceptive slasher whom you'd swear was the prototype for Curtis Martin, Warner amassed 6,705 rushing yards in a Seattle career that began as a first-round pick out of Penn State in '83 - and ended six years and one severe knee injury later.

After running for an AFC-best 1,449 yards as a rookie, Warner destroyed his knee while catching his cleat on a seam in the dangerous Kingdome turf 10 carries into the opener in his sophomore season. His career was thought to be in jeopardy, but he came back in '85 and recaptured his old form in '86 with 1,481 yards and 13 TDs. But while the numbers were impressive, the knee was never the same, and it became a chronic problem over time. The Seahawks let him go at the end of the '89 season, and he played out the string in an uneventful seven-game stint with the Rams in '90. His career was over at age 29.

While Warner's tale is sad, Easley's teetered toward tragic for a time. The Seahawks' first-round pick out of UCLA in '81, he quickly established himself as the hardest-hitting safeties in the league - think Rodney Harrison with a cornerback's speed. He was AFC defensive rookie of the year in '81, and NFL Defensive Player of the Year in '84. How respected - or maybe the better word is feared - was Easley during his prime? Ronnie Lott, someone who knows a thing or two about quality safety play, insists to this day that he was never Easley's equal on the football field. The sentiment was not unique.

While Warner's tale is sad, Easley's teetered toward tragic for a time. The Seahawks' first-round pick out of UCLA in '81, he quickly established himself as the hardest-hitting safeties in the league - think Rodney Harrison with a cornerback's speed. He was AFC defensive rookie of the year in '81, and NFL Defensive Player of the Year in '84. How respected - or maybe the better word is feared - was Easley during his prime? Ronnie Lott, someone who knows a thing or two about quality safety play, insists to this day that he was never Easley's equal on the football field. The sentiment was not unique.Lott, of course, is in the Hall of Fame, and for a time it seemed Easley would travel a similar path to football immortality. He made five Pro Bowls in his seven ('81-'87) seasons in Seattle, and it was reasonable to believe his storybook career would conclude with a celebration in Canton.

But the final chapter came sooner than anyone planned. Easley's career ended abruptly in '88 when it was revealed he needed a kidney transplant. Like Warner, he was finished at 29.

Then it got messy. Easley sued the Seahawks, contending his kidney problems were the result of doctors encouraging excessive use of ibuprofin to treat an earlier injury. It was only in 2001 that the player regarded as the most talented Seahawk of all reconciled with the franchise and took his rightful place in the team's Ring of Honor.

During these, far and away the Seahawks' headiest days, here's hoping someone shakes the cobwebs off the history books and permits these forgotten and overlooked heroes share in the spotlight during the Super Bowl festivities.

Curt Warner and Kenny Easley had their time cut short. Why not treat them to a little bit more glory now?

|

<< Home