Fallen Angel

I think most columnists (and writers in general) are overly self-critical, often unsatisfied with their own work. I fall into that category much more often than not. Reading a column post-publication, I inevitably wish I'd changed a word here, made a tweak there, and suddenly, a piece I thought I liked is is source of nagging aggravation, a missed opportunity. Sometimes though, even us hacks do find the words we were looking for, and that swing for the fence pays off with a satisfying trot around the bases. This column, published in the Concord Monitor. Oct. 23, 2002, is one of those instances for me. Ostensibly about the "cursed" Angels' 2002 World Series run, it will become apparent as you read it that it was a roundabout way for me to write about a subject close to my heart - the late, coulda-been-great Lyman Bostock. Few columns I've written have meant more to me personally. - CF

* * *

I was 8 in the summer of '78, and in my small universe, there was baseball, and then there was the unimportant stuff. Jim Rice was Batman. Butch Hobson was diving noggin-first into bat racks. Luis Tiant whirled and twirled and fooled 'em all, and the Yankees were 25 pinstriped Darth Vaders.

Baseball, especially those obviously invincible Red Sox, was on my brain so much, I might as well have had 216 red stitches winding around my head. This obsession exasperated my mom. After one too many questions about why a curveball curved or how Oscar Gamble grew such a spectacular Afro, my folks instituted a rule: No talking about baseball at the dinner table. Dinner was family time, the hour to talk about more important matters.

I didn't understand it then - what could possibly be more important than baseball? - but as the summer faded into autumn, I learned that it indeed was not life and death after all. It took the latter to teach me so.

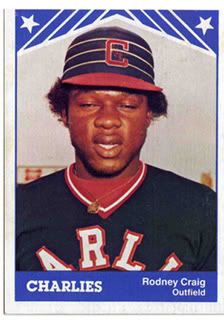

On Sept. 23, 1978, Angels outfielder Lyman Bostock was murdered. It is one of the most tragic chapters in baseball history.

On the final day of his life, a sunny Saturday afternoon, Bostock went 2-for-4 in an Angels' loss to the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. After the game and with a rare night off, he made the short drive to Gary, Ind., to visit his uncle, Thomas Turner.

At approximately 10:30 p.m., Bostock was riding in a car with Turner and his godchildren, Joan Hawkins and Barbara Smith. Bostock had known the women for 20 minutes.

A car pulled alongside. Barbara Smith could see her estranged husband, Leonard Smith, was driving. She told Turner not to stop the car. He sped through two red lights, but was forced to stop at a busy intersection.

Leonard Smith jumped out of his car and walked toward Turner's Buick. He was carrying a 12-gauge shotgun. No words were exchanged. Smith opened fire through the back window. Bostock was hit in the right temple. He crumpled to the floor, blood gushing from his head.

Three hours later, one of baseball's most appealing young stars was dead. He was 27 years old.

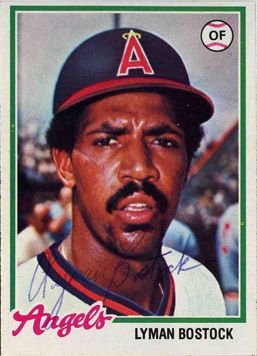

Until the day Bostock died, I knew him only as a comically airbrushed picture in my baseball card collection. But as I absorbed the finality of it all - Dead? A major-league baseball player? Is that possible? - I was hit with emotions I was not completely familiar with.

I was curious and confused and stunned and frightened and angry. His death was beyond my naive comprehension. I recall staring at that '78 Topps card endlessly, trying to memorize his stats. At the dinner table, I asked questions about Bostock. Countless questions. They had nothing to do with baseball.

Now, I imagine you're asking: Why bring up this story now? Simple. Because the current Angels - these Amazin' Angels - have brought it back to me.

These are the good old days for the 41-year-old franchise. It is a joyous time of fresh October stars such as Garret Anderson and Francisco Rodriguez, and cuddly mascots such as the Rally Monkey and David Eckstein. This year, the Angels' laughter hasn't turned to tears.

But with good times come remembrances of the bad, and heaven knows the Angels have had more than their share.

The Angels' history is so hellish, the Red Sox look blessed by comparison. We are familiar with the suicide of Donnie Moore, and all the late-season collapses. We hear about the womanizing washout Bo Belinsky, and the untimely deaths of so many promising prospects in the '70s.

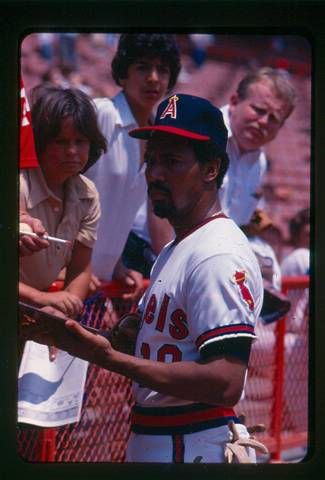

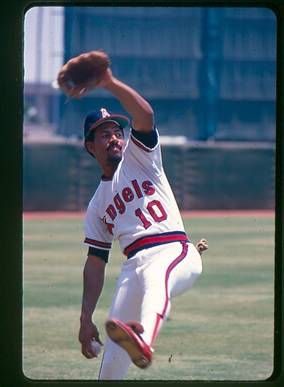

We hear about Bostock, too. But not as much as we should. He deserves to be more than a footnote, a name on a morbid list of Ballplayers Who Died During A Season. He deserves better, because he might have been among the best.

Bostock played just four major league seasons, three with Minnesota and his final one with the Angels. He died with a career .311 average - a number that pairs him with Jackie Robinson in the history books.

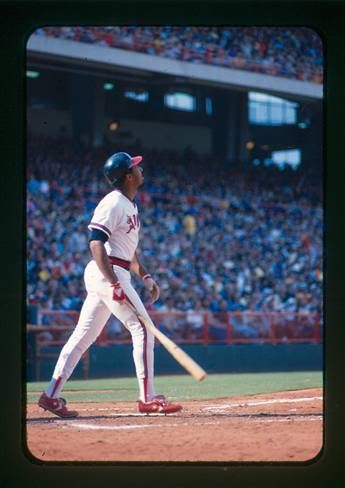

He batted .336 in 1977 and was the runner-up to teammate Rod Carew for the American League batting title. A lefty hitter with an elegant swing, he was so gifted and dedicated that his manager, Gene Mauch, compared him to Pete Rose.

Bostock could have been a great, if only that bright future had been a match for his darker fate. Maybe he would have grown up to be Tony Gwynn, a winner of multiple batting titles and a wonderful ambassador for the game. Or maybe he might have been Roberto Clemente, another doomed ballplayer whose talent was matched only by his generosity.

Kindness was among Bostock's dominant traits. After playing out his $20,000-a-year contract with the Twins - yes, that's 20 thousand, not 20 million - Bostock signed a five-year, $2.25 million deal with the Angels in November 1977. The deal, which came at the advent of big-bucks free agency, made him the third-highest-paid player in the game.

Bostock didn't intend to collect his riches. He intended to earn them. So when he began the '78 season in a 2-for-39 slump, he approached Angels owner Gene Autry and insisted on giving back his April salary.

Autry refused the offer, so Bostock decided he would give the money to charity. ("Charity The Big Winner in Bostock Slump," said the headline in The Sporting News.) Naturally, mailbags full of requests poured in, and Bostock sorted through them himself, trying to determine who needed the money the most.

A newspaper photo a few days after he died showed Bostock's jersey hanging in his locker. On the floor were several boxes of mail. His April salary was donated posthumously.

The tale of Bostock's philanthropy sounds like the stuff of fiction, particularly in the context of today's greed. The game has changed so much in the 24 years since he died, and much to its own detriment. But some things, they never change.

Baseball survives, even thrives, in spite of itself. The Red Sox crumble like a dried-up leaf in September, no matter how many promises they make in April. And much to my girlfriend's chagrin, I still babble on relentlessly about baseball at the dinner table.

Lately, the topic has been these admirable Angels, and their quest for their first World Championship. Often, I've found my windy monologues winding around to Bostock, and the summer of '78, and all that I learned about baseball, and life.

Bostock taught me that the world was cruel and unfair and unpredictable. That the good guy didn't always win, that ballplayers weren't superheroes even if they tried to be, that death can find you anywhere, anytime, even at a busy intersection on a laid-back Saturday night.

The Red Sox would stomp on my little heart later that summer, and damned if it hasn't become an annual tradition. But these Angels, the cursed Angels . . . they've kind of grown on us cynical New Englanders, haven't they? We can relate to them, appreciate what their franchise and its fans have gone through.

We are kindred spirits. They should give us hope. If the Angels can win it, well, hell, maybe the Red Sox can too.

Cheer them on, Red Sox fans. Shake those silly ThunderStix. Salute Glaus and Salmon and Percival and Spiezio. Appreciate them for doing what our hometown team could not. Applaud them for dethroning the Yankees, who are still 25 Darth Vaders, only with much larger bank accounts.

With the Angels just a couple wins away from a celebration unlike any they've ever seen, please, take a second to remember a fallen Angel from the franchise's terribly tragic past.

Remember Lyman Bostock, a wonderful ballplayer and a better man, one who had the green light to stardom, if only the red light had changed.

Labels: Butch Hobson, Lyman Bostock, Rod Carew

|

<< Home