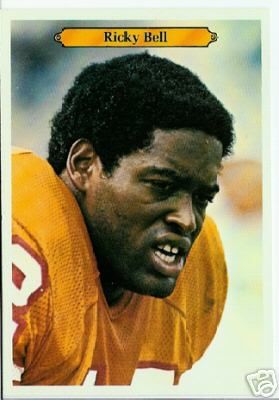

TATB Hall of Fame inductee Ricky Bell

Athletes possess the power to touch children's lives so effortlessly. Yet for those who care only halfheartedly, their influence is too often fleeting.

Athletes possess the power to touch children's lives so effortlessly. Yet for those who care only halfheartedly, their influence is too often fleeting.Sure, Mr. Big Shot can show up for a charity event, scribble some autographs, maybe read a few pages of the Cat In The Hat, flash that megawatt grin for the photo that'll be in the next morning's Names And Faces. It's all cool.

But once the shutters stop clicking and their team-mandated community service requirement is met, too many slide into the familiar comforts of the lifestyle of the rich and famous, oblivious or indifferent to the powers they hold over their young fans. It's enough to turn a starstruck fan into a bitter cynic - or God forbid, a sports-talk radio host.

If only there were more athletes who wholeheartedly embraced being heroes and role models. If only there were more sincere men, more good men in professional sports, more men who give back more then they take.

More men like Ricky Bell.

If you only vaguely remember Bell, there's no need to turn in your playbook. His NFL career lasted but six seasons (1977-82). Not long after its conclusion we'd learn it was due to a terribly tragic whim of fate, and for nearly two decades now he's been little more than a footnote in the margins of the NFL Encylopedia.

Bell's professional career began with great fanfare, but not much good fortune. The Buccaneers chose him first overall in the 1977 NFL draft, a pick ahead of Dorsett, who went to Dallas. While Tom Landry's locked and loaded Cowboys won the Super Bowl in Dorsett's first season, the Bell's Bucs were a running, stumbling joke, what with their traffic-cone orange uniforms, their something less than masculine mascot Bucco Bruce, and a 26-game losing streak that kicked off their existence.

They didn't earn their first victory until the second-to-last game of the season in Bell's rookie year. But suddenly, in 1979, the joke was on the Bucs' opponents. Bell, a fierce, relentless runner (think Ricky Williams, pre-Reefer Madness) churned his way to 1,263 yards as Tampa Bay became the darlings of the NFL, finishing one victory shy of a Super Bowl berth.

The good times didn't last - Bell became injury prone and mysteriously ill, and he and the Bucs slipped into irrelevance. But unlike so many athletes past and present, Bell's legacy is not dependent on his on-field accomplishments. It is in his friendship with a shy disabled boy named Ryan Blankenship, the details of which are both heartwarming and heartbreaking. The relationship documented in A Triumph Of The Heart: The Ricky Bell Story a 1991 TV movie starring Mario Van Peebles (a destitute man's Denzel), as well as in the following snippet from a terrific 2004 feature published by the Tampa Tribune:

Giving back. That was Bell's idea the first day he met Ryan Blankenship. It happened so accidentally. Bell's business partner, Les Roth, inquired at HRS about Bell's desire to begin a relationship with a needy child. Hours earlier, the HRS worker was at lunch with Blankenship's speech therapist. The connection was made. When Bell first visited the home, Blankenship was frightened by the sight of a hulking football player. Blankenship hid underneath his father's truck.

Bell got on his hands and knees to pull out Blankenship. Bell smiled at the boy. That's all it took to spark a friendship. Blankenship never was frightened again. When Bell grew up, he stuttered. It left scars and was the reason he majored in speech communication at USC. He was drawn to Blankenship, who struggled to form words and sounds. "They could actually communicate with smiles, with their eyes," said Carole Blankenship, Ryan's mother. "It was kind of magical."

Bell organized car washes that raised money to purchase a computer for Blankenship. He offered a standing invitation to attend Bucs practice and brought him around the locker room. Bell pushed Blankenship to take up sports and stay active. Put your mind to it, Bell said, and you can beat anything. No one knew it then, but Bell was about to face his own obstacle, one he couldn't defeat.

An obstacle he couldn't defeat. The irony of it all was so cruel. While the young boy was blossoming, the larger-than-life football hero who had gently helped bring him out of his shell was losing strength by the day.

As his football talents eroded and the injuries mounted to the point where some who knew better whispered he was a malingerer, Bell learned something was terribly wrong. The devastating diagnosis came in the immediate weeks after he retired from the San Diego Chargers during the strike in '82. He was suffering from dermatomyositis, a particularly vile disease which causes progressive hardening of the skin and muscles. It was terminal.

Ricky Bell died of cardiac arrest on Nov. 28, 1984. He was 29 years old.

It was a terrible loss for reasons that have nothing to do with football. If there is any solace in such a tragedy, it must be this:

His heart failed him. It never failed anyone else.

Twenty-one years after his hero's death, Ryan Blankenship is living proof.

|

<< Home